Plasma physicist and data analysis tool-builder

I am a researcher at MIT working on questions of data analysis related to plasma physics and nuclear fusion. I am excited by building general-purpose data analysis tools which help both my research and that of others.

My interests

- Data analysis, machine learning, statistics and Bayesian inference: I am very passionate about data analysis and getting the statistics right – everything in science is garbage in, garbage out. So, if the data are not handled correctly, the conclusions drawn will be worthless.

- Instrumentation: Without the right data coming in, no amount of clever statistics will save you, so I am very interested in working with the latest technologies and building statistical models which can incorporate all of the data which are being collected.

- Tool-building: While working on my PhD, I wrote several general-purpose, open-source analysis codes which now have users around the world. The fact that what I am doing helps people working in many fields inspires me to keep writing top-quality code.

Nuclear fusion and plasma physics research

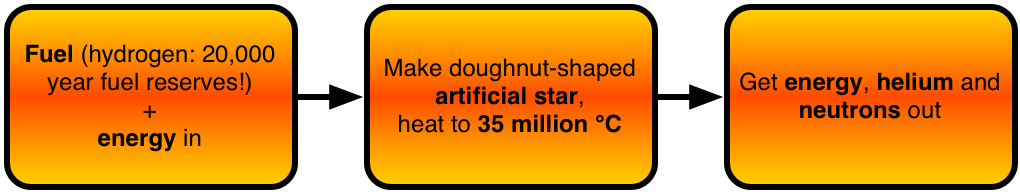

Imagine harnessing the same reactions which power the Sun to produce energy on Earth which does not stop on cloudy days. Imagine a device which can make an artificial star which burns the most abundant element in the universe (hydrogen) to produce clean, safe energy. This is what we are working on at the MIT PSFC (and numerous other labs throughout the world): nuclear fusion energy.

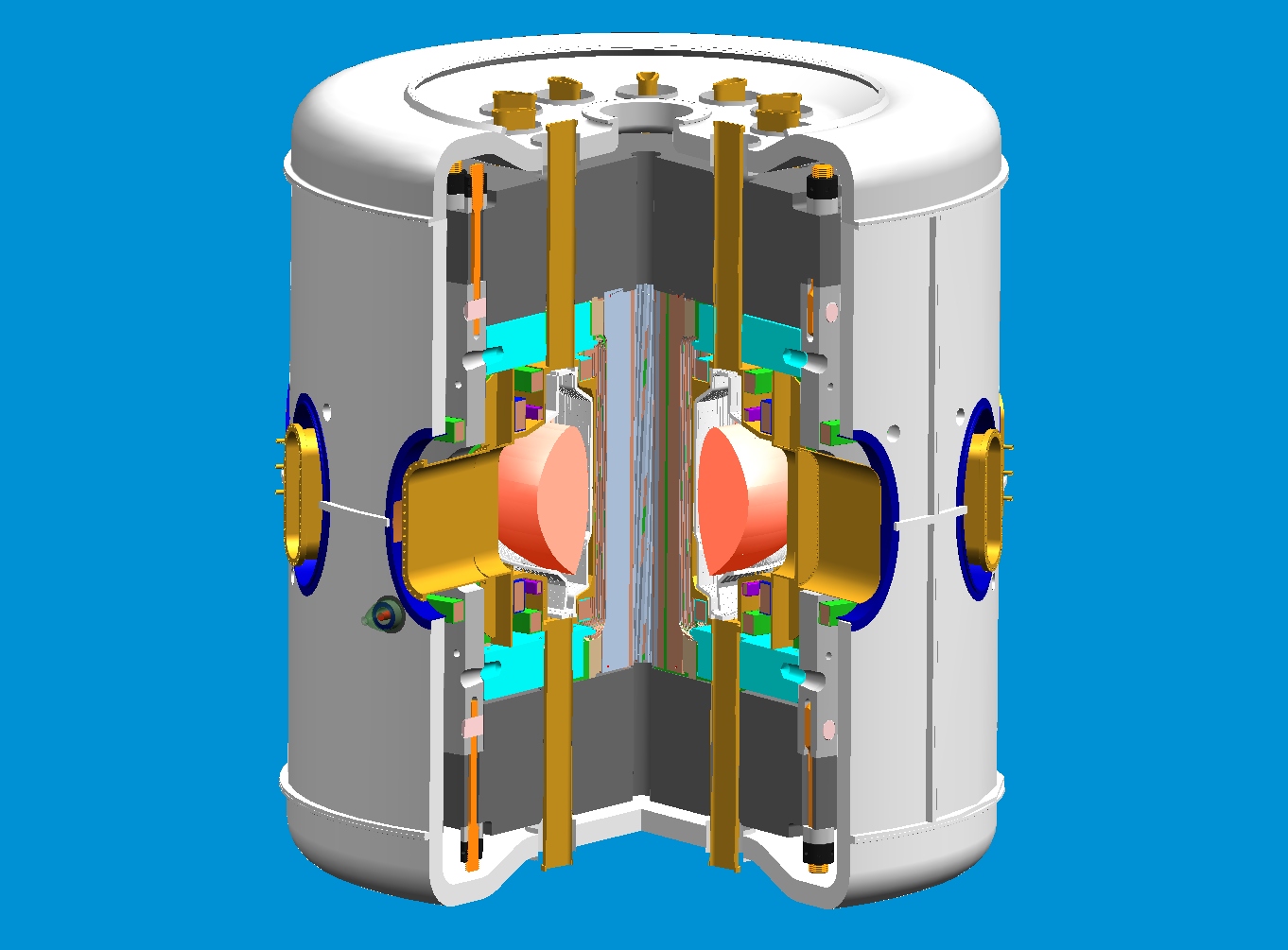

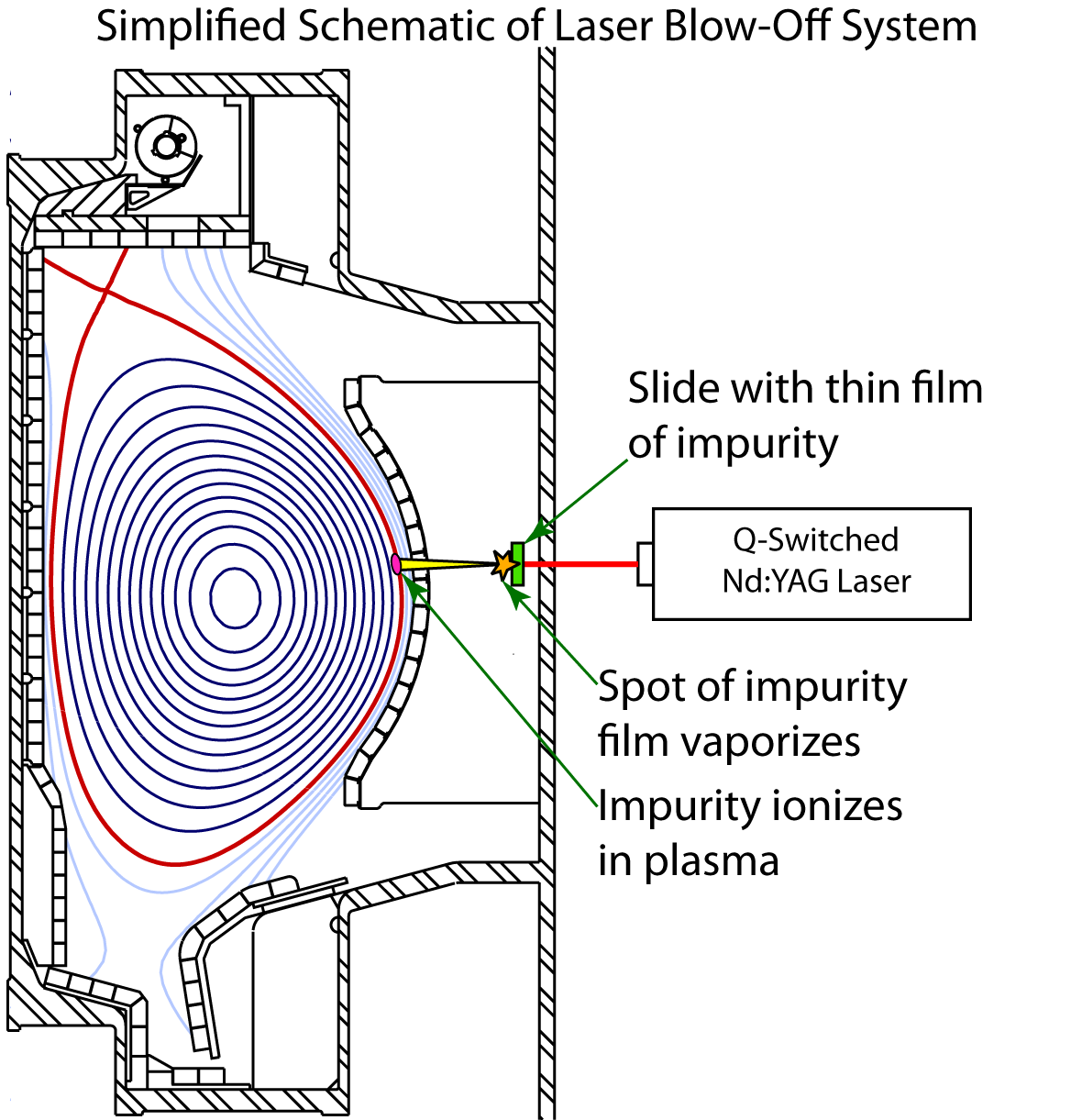

We do this using magnetic fields to hold super-hot plasma in place. If you just had a linear plasma, the particles would leak out the ends, so the plasma is bent into the shape of a doughnut: a configuration known as the tokamak. Here is a cutaway of the Alcator C-Mod tokamak I work on:

(Image courtesy of the Alcator C-Mod engineering team and released under CC license on Wikimedia.)

The plasma is the red part in the middle, everything else is part of the system that provides the magnetic field to hold the plasma in place and heat it up as hot as the Sun.

One of the biggest obstacles we have yet to overcome is how to get the reactor to produce energy faster than it leaks out. The larger the reactor is, the longer the distance particles have to move to leak out (carrying their energy with them). This motivates making fusion experiments bigger and bigger, with the result being that the next-generation experiment presently under construction is one of the most expensive scientific projects ever undertaken.

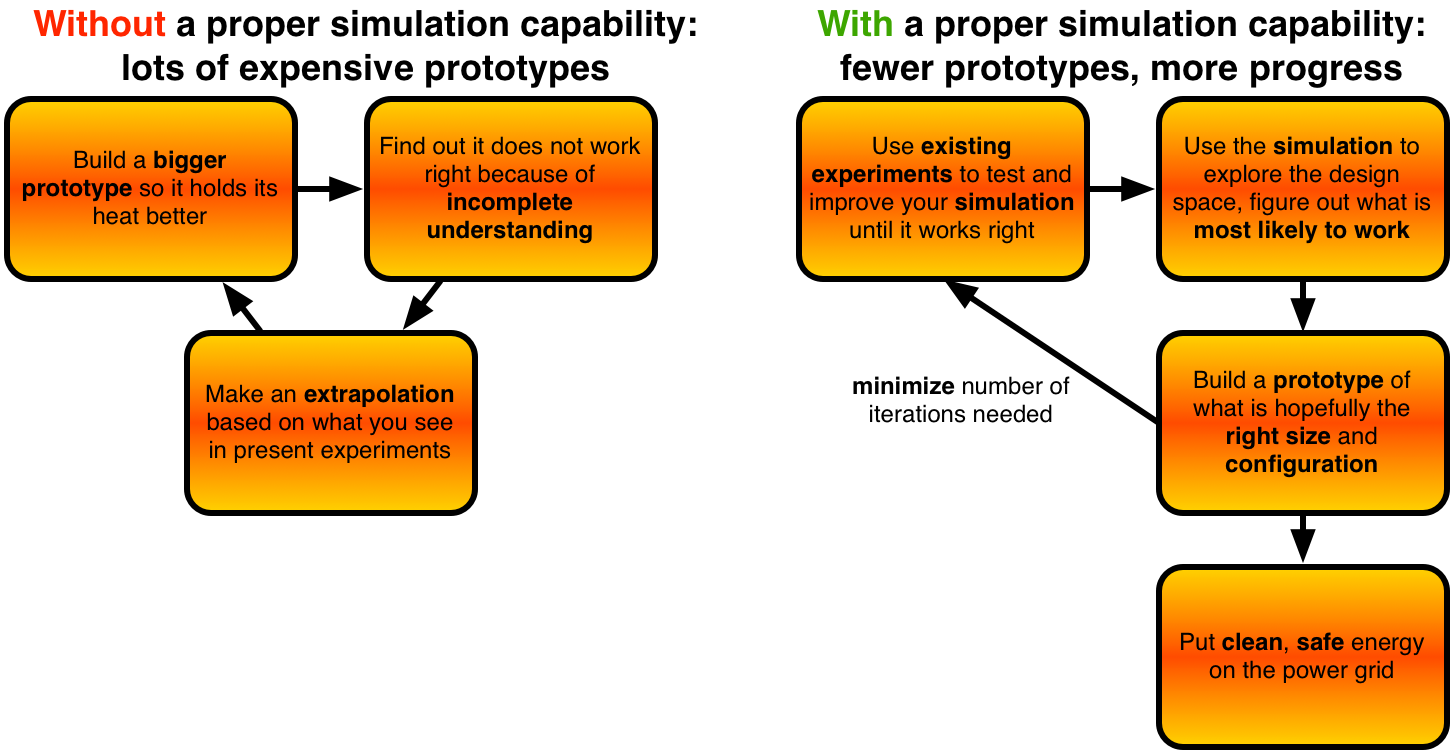

Because $10 billion is way too expensive for a 100 MW power plant (no matter how clean and safe the technology is), it is critical find ways to make fusion power in smaller, cheaper reactors. This is what inspires me to work on testing simulations of nuclear fusion reactors against the real thing: if we can properly simulate the workings of a fusion reactor, we can minimize the number of expensive prototypes we have to build before we can finally put clean, safe fusion power on the grid.

My research

My research involves bringing cutting-edge statistical tools to bear on questions of data analysis and instrumentation in order to make measurements which allow us to benchmark such simulation codes against what happens in real experiments.

Inferring plasma profiles

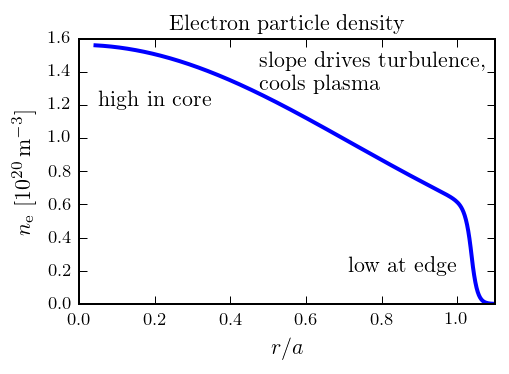

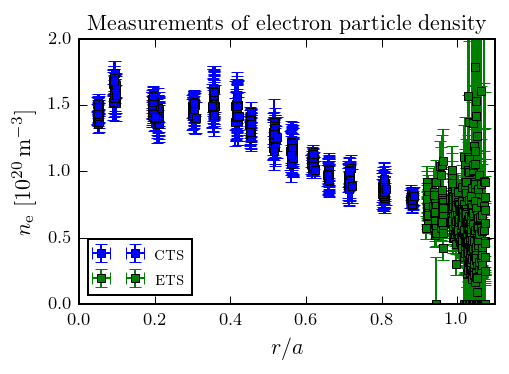

In a confined plasma, the density as a function of distance from the center of the plasma looks a little like this:

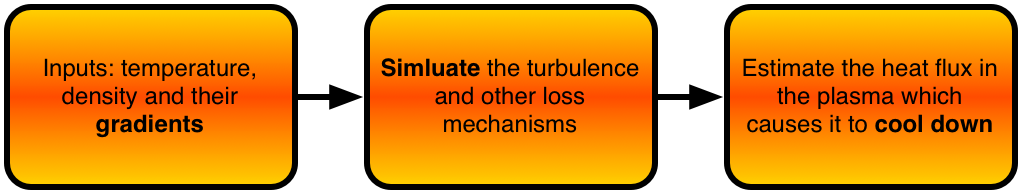

The density tapers from a high value in the center of the plasma to a near-perfect vacuum at the edge. The temperature (and hence pressure) look similar. The gradients of these profiles drive the turbulence in the plasma which causes it to cool down. Therefore, the profile gradients are critical inputs to our simulation codes:

The problem is that there are no measurements which are directly sensitive to the gradients. All we can measure are the local values as a function of space and time:

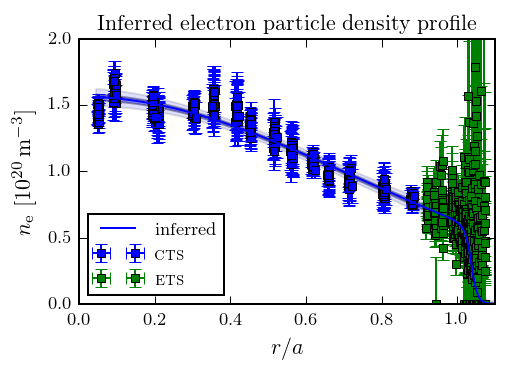

When I first started working on Alcator C-Mod, I rapidly realized that the existing techniques for estimating the uncertainties in profile gradients were woefully inadequate. To solve this problem, I pioneered the use of non-stationary Gaussian process regression combined with Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling of the hyperparameters to infer plasma profiles:

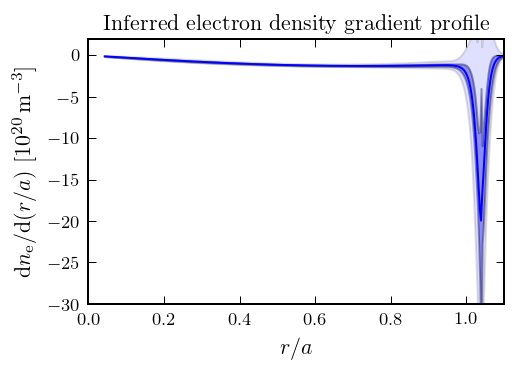

And their gradients:

This work culminated in the development of my gptools and profiletools software.

Inferring impurity transport coefficients

Imagine that you are trying to figure out what is going on in a complicated, turbulent fluid flow. A very common approach to studying this is to scatter pellets in the fluid and track them with a camera.

Now imagine the fluid is a plasma as hot as the Sun. This is the basic premise of what my project is trying to do. Instead of putting solid pellets into the plasma, I use a laser to ablate a small amount of an impurity (i.e., something different than the hydrogen fuel). And, instead of using a simple camera, I use an x-ray spectrometer to track the impurities.

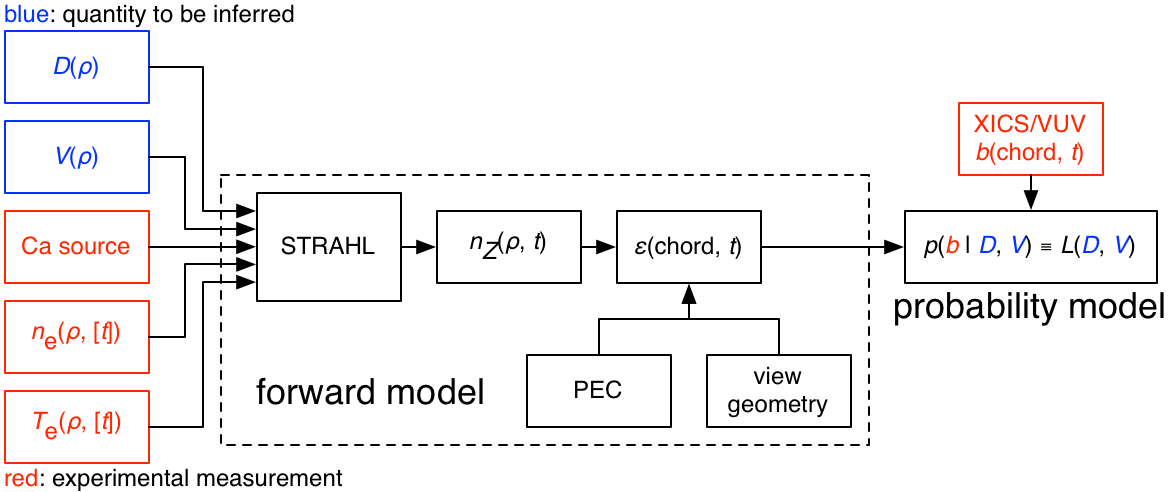

Given our measurements of how the injected impurities move, I then try to infer the diffusive and convective components of the flow so that we can compare these quantities to theoretical and computational predictions. This is a nonlinear inverse problem: given observations of how the impurities move, I am trying to infer what the underlying parameters governing that movement are.

Given measurements of the line brightnesses b, I use powerful tools such as MultiNest to attempt to find the posterior distribution for the profiles of the diffusion D and convection V which gave rise to them.

When I started work on this problem, I soon realized that the way it has traditionally been solved did not give an accurate accounting of the uncertainty and failed to account for the fact that the posterior distribution can end up having multiple solutions which match the data equally well. This can end up having a substantial, negative impact when incorrect inferences are used to benchmark simulation codes, and so the bulk of my work lately has consisted of characterizing this problem and figuring out what the bounds on what we can actually measure are.